Online Privacy Through OPSEC and Compartmentalization: Part 3

Advanced

mirimir (gpg key 0x17C2E43E)

Online Privacy Through OPSEC with Compartmentalization Among Multiple Personas

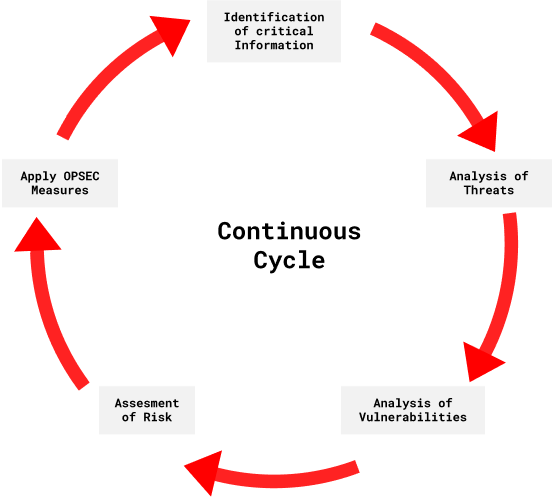

Common themes in these examples are poor planning, wishful thinking, and carelessness. Given the advantage of hindsight, it’s clear that these people were not paying enough attention. They weren’t planning ahead, and thinking things through. That is, their Operations Security (OPSEC) was horrible. Basically, OPSEC is just common sense. But it’s common sense that’s organized into a structured process. An authoritative source is arguably the DoD Operations Security (OPSEC) Program Manual. OPSEC Professionals also has a slide deck, which is comprehensive and well-presented, but somewhat campy. It points out that the OPSEC “5-Step Process” is more accurately described as a continuous cycle of identification [of information that must be secured], analysis [of threats, vulnerabilities and risks] and remediation. That is, OPSEC is a way of being. For a hacker perspective, I recommend the grugq’s classic OPSEC for hackers. Also great are follow-on interviews in Blogs of War and Privacy PC.

Another great source is 73 Rules of Spycraft by Allen Dulles. Also see the original article about them by James Srodes, from the Intelligencer. Allen Dulles played a key intelligence role against Germany during WWII, and then in the Cold War, as the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence. He’s rather controversial, especially regarding his role in the Bay of Pigs fiasco, and perhaps the JFK assassination. David Talbot wrote a biography, The Devil’s Chessboard. And later opined: “I think that you can make a case, although I didn’t explicitly say this in the book, for Allen Dulles being a psychopath.” The CIA predictably disagreed, albeit rather politely. But noted progressive Joseph Palermo fundamentally agreed with Talbot’s assessment: “The Devil’s Chessboard is quite simply the best single volume I’ve come across that details the morally bankrupt and cynical rise of an activist intelligence apparatus in this country that was not only capable of intervening clandestinely in the internal affairs of other nations but domestically too.” Be that as it may, Allen Dulles had some excellent insights about OPSEC. At least, if you ignore the parts about managing human “assets”.

Identification of Critical Information, Analysis of Threats, and Identification of Vulnerabilities

The first step is the identification of information that must be secured. See the DoD OPSEC manual at p. 12. For our purposes, critical information fundamentally comprises one’s meatspace identity and location. Also critical are public indicators associated with them. For example, consider Ross Ulbricht. FBI investigators pieced together his posts as altoid on Bitcoin Forum to associate Silk Road with rossulbricht@gmail.com. They also pieced together frosty@frosty’s SSH key on the Silk Road server with the frosty frosty@frosty.com account on Stack Overflow, which he had initially registered as Ross Ulbricht. That is, the indicators were altoid and frosty. Or consider Shannon McCoole. Investigators pieced together posts on The Love Zone and 4WD forums, using his username (~skee) and his characteristic greeting (hiyas). Then they found his personal Facebook page, by searching for SKUs of particular 4WD lift kits that he had posted about. So for him, the indicators were skee, hiyas, and the SKUs. For Sabu, an IRC admin pieced together his various nicknames, over time, to link his current nickname/persona with his meatspace identity, which had been revealed years before.

The next steps are analysis of threats, and identification of vulnerabilities. From the DoD OPSEC manual at p. 13:

The threat analysis includes identifying potential adversaries and their associated capabilities and intentions to collect, analyze, and exploit critical information and indicators.

Wherever adversaries can collect and effectively exploit critical information and/or indicators, there are vulnerabilities. So who are your adversaries? And what are their capabilities? Anyone interested in you, with goals that you reject and fear, is an adversary. You probably have some sense of who they are, what they want, and what they can do. But what matters? In an interview with Micah Lee, Edward Snowden observed:

Almost every principle of operating security is to think about vulnerability. Think about what the risks of compromise are and how to mitigate them. In every step, in every action, in every point involved, in every point of decision, you have to stop and reflect and think, “What would be the impact if my adversary were aware of my activities?” If that impact is something that’s not survivable, either you have to change or refrain from that activity, you have to mitigate that through some kind of tools or system to protect the information and reduce the risk of compromise, or ultimately, you have to accept the risk of discovery and have a plan to mitigate the response. Because sometimes you can’t always keep something secret, but you can plan your response.

Anyway, none of that is possible without plans. Or at least, it’s impossible without some sense of what one’s plans will be. As Allen Dulles noted:

- Never set a thing really going, whether it be big or small, before you see it in its details. Do not count on luck. Or only on bad luck.

This is arguably a central theme in all of my pwnage examples. When one is just playing around, with no real plans, or not even a clear sense of what one might plan, one may not worry enough about protecting one’s identity. And after one gets serious, and the stakes get higher, one may forget about just how lax one’s OPSEC was. So do plan ahead, and think things through.

The final steps are risk assessment, and identification of countermeasures. From the DoD OPSEC manual at p. 13:

The risk assessment is the process of evaluating the risks to information based on susceptibility to intelligence collection and the anticipated severity of loss. It involves assessing the adversary’s ability to exploit vulnerabilities that would lead to the exposure of critical information and the potential impact it would have on the mission. Determining the level of risk is a key element of the OPSEC process and provides justification for the use of countermeasures. Once the amount of risk is determined, consider cost, time, and effort of implementing OPSEC countermeasures to mitigate risk.

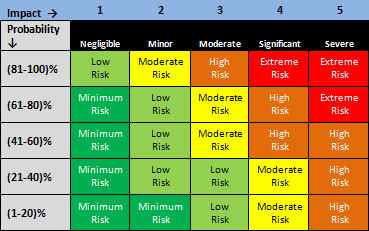

That is, risks are characterized by their likelihood aka probability, and their potential impact. To help prioritize risks and identify countermeasures, it’s common to visualize them, plotting probability vs impact. From Mind Tools:

The corners of the chart have these characteristics:

- Low impact/low probability – Risks in the bottom left corner are low level, and you can often ignore them.

- Low impact/high probability – Risks in the top left corner are of moderate importance – if these things happen, you can cope with them and move on. However, you should try to reduce the likelihood that they’ll occur.

- High impact/low probability – Risks in the bottom right corner are of high importance if they do occur, but they’re very unlikely to happen. For these, however, you should do what you can to reduce the impact they’ll have if they do occur, and you should have contingency plans in place just in case they do.

- High impact/high probability – Risks towards the top right corner are of critical importance. These are your top priorities, and are risks that you must pay close attention to.

High-impact/low-probability risks are highly problematic:

[I]t may often be easier to characterise the impact of an event than its likelihood, such as the impact of your wallet being stolen against working out the numerical likelihood of it happening. … People are often unwilling to give credence to improbable notions specifically because their professional or social community consider them too improbable. … In addition, if a problem is thought too complex, there is the danger that organizations will simply ignore it. … More generally, there is often a lack of imagination when considering high impact low probability risks. [emphasis added]

The US National Security Agency (NSA) arguably poses an existentially high-impact/low-probability risk for virtually everyone. That may seem too improbable, but it’s certainly existential, and so worth discussion. But do keep in mind Allen Dulles’ rule 72:

If anything, overestimate the opposition. Certainly never underestimate it. But do not let that lead to nervousness or lack of confidence. Don’t get rattled, and know that with hard work, calmness, and by never irrevocably compromising yourself, you can always, always best them.

Is the NSA Your Adversary? Consider the Risks of Data Sharing and Parallel Construction

The NSA is responsible for military signals intelligence (SIGINT). Initially, it was known (at least jokingly) as ‘No Such Agency’, the stuff of conspiracy theories. For obvious reasons, its capabilities and activities are largely classified. We know about them primarily from James Bamford’s books, from such whistleblowers as Bill Binney, Kirk Wiebe and Thomas Drake, and from materials leaked by Edward Snowden and The Shadow Brokers. So our understanding is limited. But even so, the NSA’s capabilities are mind-boggling. More links about NSA are here.

The NSA is a global active adversary. That is, it can (in principle, anyway) intercept, modify and trace all Internet traffic. It has a global grid of computers that intercept data from the Internet, store it, process it, and make it available to analysts. Using intercepts from network edges, it can employ traffic analysis to de-anonymize any persistent low-latency connection, no matter how much it’s been rerouted. And it can arguably compromise any networked device, and exploit it to get additional information. Also, it actively targets system administrators, in order to access to networks that they administer.

However, while the NSA arguably intercepts everyone’s online activity, it can’t collect it all in a single location, because that would require implausibly fat pipes and humongous storage. And it can’t de-anonymize all low-latency connections, because that would require implausible processing power. But analysts can operate in parallel on all grid components, and receive results for local analysis. Data of interest gets moved to centralized long-term storage. But even the NSA can’t store all intercept data indefinitely. So its systems prioritize, and then triage. Data that seems more important is retained longer. But all metadata (time, IP addresses, headers, and so on) are retained indefinitely. And so are data that seem most important. That reportedly includes all encrypted data (but not all HTTPS, I suspect) that could not be decrypted (plus associated unencrypted metadata).

The good news is that the NSA’s charge is national security, and that you are most likely far too insignificant to warrant its attention. However, it’s important to note that the NSA does retain and search data on American residents. Also see this excellent article, and the declassified Memorandum Opinion and Order from the FISA Court. This is supposedly accidental, or incidental, or unavoidable, or something like that. And the FISA Court says to stop. Not that it matters much to the rest of us.

But anyway, who else has access to all this data? Well, we know that the NSA shares with intelligence agencies of US allies. And also gets data collected by them. There are at least three groups of such allies:

- Five Eyes (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States)

- Nine Eyes (Five Eyes plus Denmark, France, the Netherlands, and Norway)

- Fourteen Eyes (Nine Eyes plus Germany, Belgium, Italy, Spain, and Sweden)

We also know that the NSA shares data with numerous US law-enforcement agencies [2013], including the DEA, DHS, FBI and IRS:

A secretive U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration unit is funneling information from intelligence intercepts, wiretaps, informants and a massive database of telephone records to authorities across the nation to help them launch criminal investigations of Americans.

Although these cases rarely involve national security issues, documents reviewed by Reuters show that law enforcement agents have been directed to conceal how such investigations truly begin - not only from defense lawyers but also sometimes from prosecutors and judges.

The undated documents show that federal agents are trained to “recreate” the investigative trail to effectively cover up where the information originated, a practice that some experts say violates a defendant’s Constitutional right to a fair trial. If defendants don’t know how an investigation began, they cannot know to ask to review potential sources of exculpatory evidence - information that could reveal entrapment, mistakes or biased witnesses.

…

The unit of the DEA that distributes the information is called the Special Operations Division, or SOD. Two dozen partner agencies comprise the unit, including the FBI, CIA, NSA, Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Homeland Security. It was created in 1994 to combat Latin American drug cartels and has grown from several dozen employees to several hundred.

Today, much of the SOD’s work is classified, and officials asked that its precise location in Virginia not be revealed. The documents reviewed by Reuters are marked “Law Enforcement Sensitive”, a government categorization that is meant to keep them confidential.

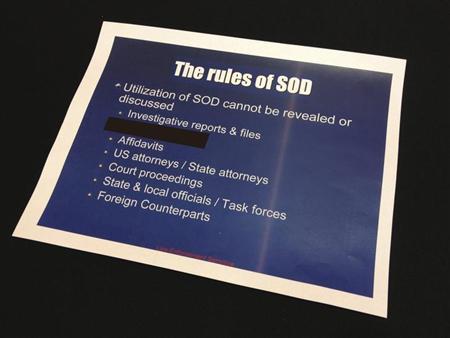

“Remember that the utilization of SOD cannot be revealed or discussed in any investigative function”, a document presented to agents reads. The document specifically directs agents to omit the SOD’s involvement from investigative reports, affidavits, discussions with prosecutors and courtroom testimony. Agents are instructed to then use “normal investigative techniques to recreate the information provided by SOD”. [emphasis added]

This is termed parallel construction. Reportedly, it’s long been a standard approach for protecting sources and investigative methods. Such as confidential informants. But the scale here is vastly larger. And the practice is arguably unconstitutional (not to mention, that it entails criminal conspiracy to suborn perjury).

But these are just nonspecific allegations, based on leaked documents and whistleblowers. Is there actually any unambiguous evidence that criminal prosecutions have secretly relied on NSA intercepts? I find nothing online. However, there is an excellent panel discussion from August 2015 at the DEA Museum website, involving former SOD directors and staff, about SOD history. John Wallace was very candid about the motivation to circumvent post-Watergate policies, which had been implemented to prevent warrantless electronic surveillance and eavesdropping on American citizens:

00:18:20 Well, we - we got to step back, and I got to give you some historical context. Remember, when we’re talking now, the early ‘90s. This is at least 10 years before 9/11, uh, and, so, we had two problems. …

00:18:50 The other dynamic that Bobby mentioned was we had, uh, the - the cases in New York, uh, principally en - engaged against the - the Cali Cartel that were simply dying on the vine in New York. Um, on the other hand, we had elements of the intelligence community who said they had all of this great information, but nothing ever came of it. Um, and, again, 10 years before 9/11, the wall is up, it is absolutely prohibited for, uh, anybody on the Intelligence side of the house, uh, to talk to somebody with a criminal investigative, uh, responsibility.

00:20:00 I was fortunate to be in a group of about four or five people, including the Attorney General, Bob Mueller was the Chief of the Criminal Division. Um, uh, uh, a true heroine in all of this was Mary Lee Warren who, at that time, uh, had the narcotics section. Uh, and, so, after meeting with Bobby’s small group, we got together with the senior leadership of CIA, the senior leadership of NSA, and the senior leadership of the Department, uh, of Justice, and began to work these two problems. [emphasis added]

00:20:35 The first problem being: How do we engage with the Intelligence community without compromising their sensitive sources and methods, their equities, without violating this - this wall arrangement; at the same time, breed [sic] life into Bill Mockler’s investigations in New York, and get the U.S. Attorneys all on the same sheet of music with regard to prosecuting these national level investigations that - that Bobby was trying to put together.

00:22:13 We don’t want to have to turn this stuff over in the course of discovery. On the same, uh, token though, the - we’ve got to make sure that the defendants’ rights to full and free discovery are completely observed. [huh?] We don’t want, uh, for example, CIA officers on the witness stand. Um, and - and those were some of the issues that we had to come up with creative solutions. Uh, and - and on occasion, uh, it, uh, it meant we’re - the solution we come at is going to be less than perfect, you know, because we want to, uh, to stay away from some of these electrified third rails on the legal side of the house.

And from Michael Horn:

00:47:31 Well, first, we - when we discussed this coordination between the Intelligence and the Operations Divisions, um, Joe referred to this - it - it was really the mantra at SOD, SOD takes no credit. We - we wanted to make sure the SACs were comfortable with - with our role in - in their investigations, and sometimes they were not. Uh, but by - by stepping back when - when these cases went down and - and assuring that any credit, any publicity, any photo ops, uh, were taken by the field, and SOD just stayed in the background, that went a long way to assuaging some of the - the SAC’s concerns. [emphasis added]

SOD has apparently been part of numerous drug cases, including major operations against cartels, but only two are named. Joseph Keefe mentioned Mountain Express:

00:51:06 A - a tremendous amount of cases. Every section that I had was fortunate they were all very productive. One that comes to mind ‘cause it involved DEA as a whole was Mount - a thing called Mountain Express. Mountain Express was back - well, Jack Riley was the ASAC.

And Michael Horn mentioned two Zorro cases:

00:53:56 Well, I guess the two Zorro cases were - which were two of the first national level cases, uh, come to mind. And, um, it - it was - again, as Joe mentioned, an incredible coordination a - among a lot of field offices. And, of course, the goal was to protect the wires that were going on. At this time, I think there were some wires going on in Los Angeles, and they were following loads to - across the country to New York. …

Even though SOD has allegedly played a major role in a tremendous number of cases since the early 90s, I find nothing online about the use of intelligence data, before the Reuters exposé in late 2013. Although some of the old drug cases are featured on the DOJ website, the use of parallel construction to hide use of intelligence data isn’t mentioned. For obvious reasons. Less than a year before the Reuters exposé, there was no mention of SOD in Senate debate on extending the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 for five years. Without doubt, at least Senator Feinstein was aware of SOD. But again, the reasons for silence are obvious.

Even since the Reuters exposé, I find nothing online about specific cases where investigators allegedly relied secretly on NSA intercepts, and engaged in parallel construction. No defense challenges. No court opinions. Not even anonymous allegations. There was a federal ruling in 2016, suppressing Stingray evidence that was obtained without a search warrant:

U.S. District Judge William Pauley in Manhattan on Tuesday ruled that defendant Raymond Lambis’ rights were violated when the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration used such a device without a warrant to find his Washington Heights apartment.

The DEA had used a stingray to identify Lambis’ apartment as the most likely location of a cell phone identified during a drug-trafficking probe. Pauley said doing so constituted an unreasonable search.

“Absent a search warrant, the government may not turn a citizen’s cell phone into a tracking device” Pauley wrote.

And yet there’s nothing online about the use of intelligence data in criminal cases. That’s surprising, given likely concerns about constitutionality, and participation in criminal conspiracy to suborn perjury. You’d think that at least one investigator would have turned whistleblower. But then, the NSA has been very careful about protecting sources and methods. I mean, consider 9/11. The NSA and CIA had allegedly monitored some of the plotters, but didn’t manage to convince Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to act. Whistleblowers claim that key results were “not disseminated outside of NSA”. Basically, I gather that the NSA had compromised parts of al Qaeda’s telephone network, and considered the intercepts too valuable to risk.

According to New America’s Open Technology Institute: “The NSA uses [Section 702] authority to surveil communications that go well beyond the national security purpose of the law.” In recent years, it appears that the FBI has further relaxed its rules for accessing NSA data. And finally, one of President Obama’s last acts was basically to normalize and expand SOD, allowing cooperating federal agencies to directly search NSA data. Perhaps he wanted to facilitate investigation of collusion of Russia and the Trump campaign.

Bottom line, it’s prudent to assume:

- The NSA intercepts all Internet data.

- All SOD partners (such as CIA, DEA, DHS, FBI and IRS) can access that data directly.

- The NSA shares data with US allies.

- Many (if not all) investigators in those countries can access NSA data.

With that in mind, how might NSA data been used in my pwnage examples? There’s been speculation that two aspects of the Silk Road investigation are implausible: 1) using Google to find altoid’s posts on the Bitcoin Forum; and 2) discovery by DHS of fake IDs sent to Ross Ulbricht. The first claim is weak, given that one can easily replicate the search. But the second seems reasonable, given that relatively few Silk Road packages were intercepted. And given that DHS and FBI are SOD partners, FBI investigators searching for Silk Road would have seen Ross Ulbricht among the hits. It’s also possible that the NSA tipped off the FBI about the Silk Road server, and how to find its IP address.

OK, what else? Well, consider Operation Onymous. Perhaps the FBI might have known, from public sources, that DOD had funded research at CMU on Tor vulnerabilities. But how would the FBI have known that CMU researchers had identified numerous illegal Tor onion services, such as Silk Road 2.0? Perhaps they saw the announced Black Hat talk, subpoenaed the results, and imposed a protective order. But in that case, why did the FBI enigmatically refer questions about Silk Road 2.0 to CMU? Evasiveness creates suspicion. Especially because this was a drug case, and the role of SOD is always hidden through parallel construction.

Next Articles

Here to learn?

Consult our guides for increasing your privacy and anonymity.

IVPN Privacy GuidesSuggest an edit on GitHub.